This post deals with mental illness and might be triggering for some readers.

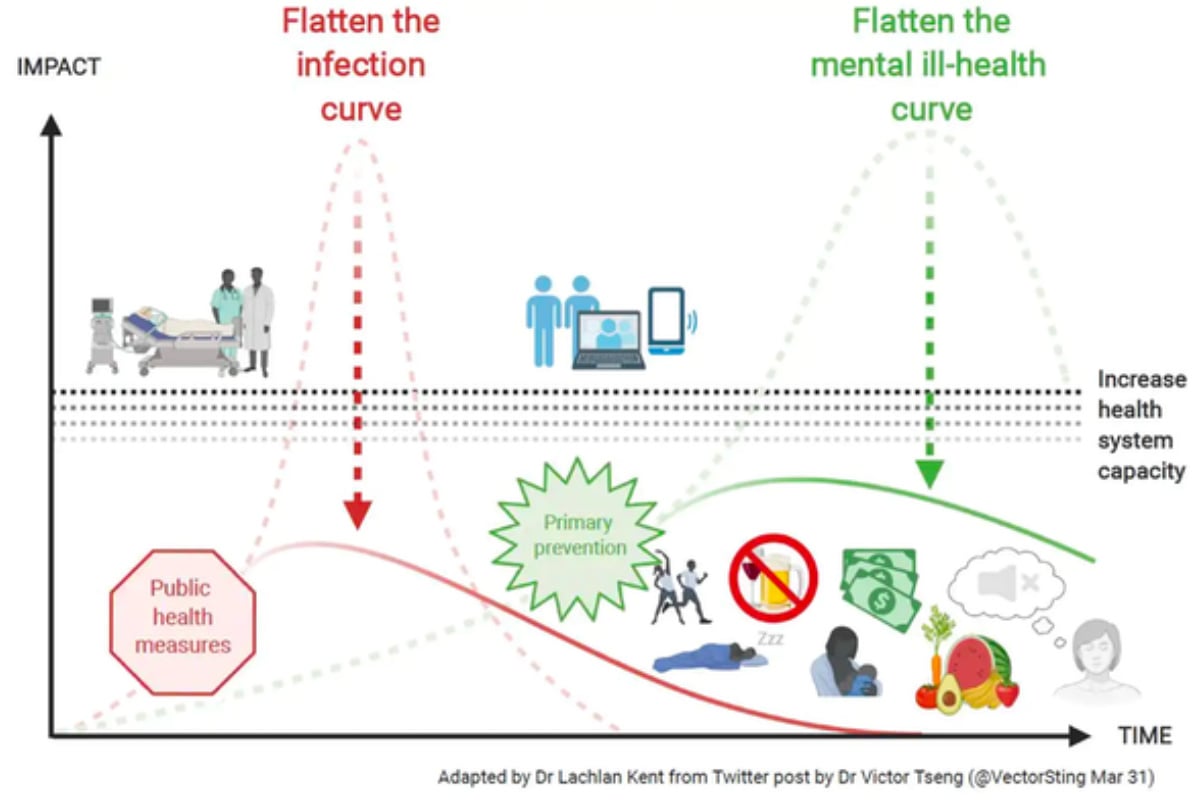

The battle against the mental health consequences of the coronavirus pandemic is just beginning. Governments and researchers are mapping how best to prevent the predicted rise in mental health issues we face in coming months and beyond.

This involves not only preventing a wave of mental disorders from starting but also preventing increased difficulties in people already living with poor mental health.

Five simple life changes to help with anxiety. Post continues below.

Is more outreach the answer, where mental health teams proactively go into the community to visit people in their homes?

Do we best focus on social policies and economic support to ease the financial and mental health pressure of job losses, isolation and increased stress?

What other evidence-based ways of flattening the mental health curve are there? And once these services start, how do we make sure people actually use them?

Here’s what we face

People are already reporting psychological distress during the pandemic. And we’re just starting to collect Australian data. One preliminary study shows about 30 per cent of survey participants have moderate to high levels of anxiety and depression. More Australian surveys are underway.